- Contemporary Fiction

- Contemporary Fiction

- Children

- Children

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Non-Fiction

- Non-Fiction

- Fiction

- Fiction

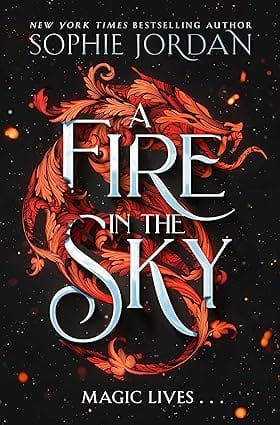

A beautiful new hardback edition of the classic Discworld novel.

Moist von Lipwig is a con artist and a fraud and a man faced with a life choice: be hanged, or put Ankh-Morpork's ailing postal service back on its feet.

It was a tough decision.

But he's got to see that the mail gets though, come rain, hail, sleet, dogs, the Post Office Workers Friendly and Benevolent Society, the evil chairman of the Grand Trunk Semaphore Company, and a midnight killer.

Getting a date with Adora Bell Dearheart would be nice, too.

Review

'Like many of Pratchett's best comic novels, it is a book about redemption ... There's a moral toughness here, which is one of the reasons why Pratchett is never merely frivolous.' - Time Out

'With all the puns, strange names and quick-fire jokes about captive letters demanding to be delivered, it's easy to miss how cross about injustice Terry Pratchett can be. This darkness and concrete morality sets his work apart from imitators of his English Absurd school of comic fantasy.' - Guardian

'Terry Pratchett is one of the great makers of what Auden called 'secondary worlds'. His inventiveness - with people with plots, with things - is seemingly inexhaustible ... Pratchett can make you giggle helplessly and then grin grimly at the sharpness of his wit. Twelve-year old boys love him, but he himself is grown up. He knows that terrible things exist and happen, and he invents a benign otherworld in which we can face them, and laugh.' - A.S. Byatt, DAILY MAIL

'Pratchett ... is the missing link between Douglas Adams and J.K. Rowling. To non-initiates his work is gobbledygook, but dig deeper and you find the wit and imaginationthat have gained him a fanatical readership - among them is A.S. Byatt.' - FT MAGAZINE

About the Author

Terry Pratchett was the acclaimed creator of the global bestselling Discworld series, the first of which, The Colour of Magic, was published in 1983. In all, he was the author of over fifty bestselling books which have sold over 100 million copies worldwide. His novels have been widely adapted for stage and screen, and he was the winner of multiple prizes, including the Carnegie Medal. He was awarded a knighthood for services to literature in 2009, although he always wryly maintained that his greatest service to literature was to avoid writing any.

www.terrypratchettbooks.com

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Angel

In which our Hero experiences Hope, the Greatest Gift — The Bacon Sandwich of Regret — Sombre Reflections on Capital Punishment from the Hangman — Famous Last Words — Our Hero Dies — Angels, conversations about — Inadvisability of Misplaced Offers regarding Broomsticks — An Unexpected Ride — A World Free of Honest Men — A Man on the Hop — There is Always a Choice

They say that the prospect of being hanged in the morning concentrates a man's mind wonderfully; unfortunately, what the mind inevitably concentrates on is that it is in a body that, in the morning, is going to be hanged.

The man going to be hanged had been named Moist von Lipwig by doting if unwise parents, but he was not going to embarrass the name, in so far as that was still possible, by being hung under it. To the world in general, and particularly on that bit of it known as the death warrant, he was Albert Spangler.

And he took a more positive approach to the situation and had concentrated his mind on the prospect of not being hanged in the morning, and most particularly on the prospect of removing all the crumbling mortar from around a stone in his cell wall with a spoon. So far the work had taken him five weeks, and reduced the spoon to something like a nail file. Fortunately, no one ever came to change the bedding here, or else they would have discovered the world's heaviest mattress. It was the large and heavy stone that was currently the object of his attentions, and at some point a huge staple had been hammered into it as an anchor for manacles.

Moist sat down facing the wall, gripped the iron ring in both hands, braced his legs against the stones on either side, and heaved.

His shoulders caught fire and a red mist filled his vision but the block slid out, with a faint and inappropriate tinkling noise. Moist managed to ease it away from the hole and peered inside.

At the far end was another block, and the mortar around it looked suspiciously strong and fresh.

Just in front of it was a new spoon. It was shiny.

As he studied it, he heard the clapping behind him. He turned his head, tendons twanging a little riff of agony, and saw several of the warders watching him through the bars.

'Well done, Mr Spangler!' said one of them. 'Ron here owes me five dollars! I told him you were a sticker! He's a sticker, I said!'

'You set this up, did you, Mr Wilkinson?' said Moist weakly, watching the glint of light on the spoon.

'Oh, not us, sir. Lord Vetinari's orders. He insists that all condemned prisoners should be offered the prospect of freedom.'

'Freedom? But there's a damn great stone through there!'

'Yes, there is that, sir, yes, there is that,' said the warder. 'It's only the prospect, you see. Not actual free freedom as such. Hah, that'd be a bit daft, eh?'

'I suppose so, yes,' said Moist. He didn't say 'you bastards.' The warders had treated him quite civilly this past six weeks, and he made a point of getting on with people. He was very, very good at it. People skills were part of his stock-in-trade; they were nearly the whole of it. Besides, these people had big sticks. So, speaking carefully, he added: 'Some people might consider this cruel, Mr Wilkinson.'

'Yes, sir, we asked him about that, sir, but he said no, it wasn't. He said it provided-' his forehead wrinkled '-occ-you-pay-shun-all ther-rap-py, healthy exercise, prevented moping and offered that greatest of all treasures which is Hope, sir.'

'Hope,' muttered Moist glumly.

'Not upset, are you, sir?'

'Upset? Why should I be upset, Mr Wilkinson?'

'Only the last bloke we had in this cell, he managed to get down that drain, sir. Very small man. Very agile.'

Moist looked at the little grid in the floor. He'd dismissed it out of hand. 'Does it lead to the river?' he said.

The warder grinned. 'You'd think so, wouldn't you? He was really upset when we fished him out. Nice to see you've entered into the spirit of the thing, sir. You've been an example to all of us, sir, the way you kept going. Stuffing all the dust in your mattress? Very clever, very tidy. Very neat. It's really cheered us up, having you in here. By the way, Mrs Wilkinson says ta very much for the fruit basket. Very posh, it is. It's got kumquats, even!'

'Don't mention it, Mr Wilkinson.'

'The Warden was a bit green about the kumquats 'cos he only got dates in his, but I told him, sir, that fruit baskets is like life: until you've got the pineapple off'f the top you never know what's underneath. He says thank you, too.'

'Glad he liked it, Mr Wilkinson,' said Moist absent-mindedly. Several of his former landladies had brought in presents for 'the poor confused boy', and Moist always invested in generosity. A career like his was all about style, after all.

'On that general subject, sir,' said Mr Wilkinson, 'me and the lads were wondering if you might like to unburden yourself, at this point in time, on the subject of the whereabouts of the place where the location of the spot is where, not to beat about the bush, you hid all that money you stole . . .?'

The jail went silent. Even the cockroaches were listening.

'No, I couldn't do that, Mr Wilkinson,' said Moist loudly, after a decent pause for dramatic effect. He tapped his jacket pocket, held up a finger and winked. The warders grinned back.

'We understand totally, sir. Now I'd get some rest if I was you, sir, 'cos we're hanging you in half an hour,' said Mr Wilkinson.

'Hey, don't I get breakfast?'

'Breakfast isn't until seven o'clock, sir,' said the warder reproachfully. 'But, tell you what, I'll do you a bacon sandwich. 'cos it's you, Mr Spangler.'

***

And now it was a few minutes before dawn and it was him being led down the short corridor and out into the little room under the scaffold. Moist realized he was looking at himself from a distance, as if part of himself was floating outside his body like a child's balloon ready, as it were, for him to let go of the string.

The room was lit by light coming through cracks in the scaffold floor above, and significantly from around the edges of the large trapdoor. The hinges of said door were being carefully oiled by a man in a hood.

He stopped when he saw the party arrive and said, 'Good morning, Mr Spangler.' He raised the hood helpfully. 'It's me, sir, Daniel "One Drop" Trooper. I am your executioner for today, sir. Don't you worry, sir. I've hanged dozens of people. We'll soon have you out of here.'

'Is it true that if a man isn't hanged after three attempts he's reprieved, Dan?' said Moist, as the executioner carefully wiped his hands on a rag.

'So I've heard, sir, so I've heard. But they don't call me One Drop for nothing, sir. And will sir be having the black bag today?'

'Will it help?'

'Some people think it makes them look more dashing, sir. And it stops that pop-eyed look. It's more a crowd thing, really. Quite a big one out there this morning. Nice piece about you in the Times yesterday, I thought. All them people saying what a nice young man you were, and everything. Er . . . would you mind signing the rope beforehand, sir? I mean, I won't have a chance to ask you afterwards, eh?'

'Signing the rope?' said Moist.

'Yessir,' said the hangman. 'It's sort of traditional. There's a lot of people out there who buy old rope. Specialist collectors, you could say. A bit strange, but it takes all sorts, eh? Worth more signed, of course.' He flourished a length of stout rope. 'I've got a special pen that signs on rope. One signature every couple of inches? Straightforward signature, no dedication needed. Worth money to me, sir. I'd be very grateful.'

'So grateful that you won't hang me, then?' said Moist, taking the pen. This got an appreciative laugh. Mr Trooper watched him sign along the length, nodding happily.

'Well done, sir, that's my pension plan you're signing there. Now . . . are we ready, everyone?'

'Not me!' said Moist quickly, to another round of general amusement.

'You're a card, Mr Spangler,' said Mr Wilkinson. 'It won't be the same without you around, and that's the truth.'

'Not for me, at any rate,' said Moist. This was, once again, treated like rapier wit. Moist sighed. 'Do you really think all this deters crime, Mr Trooper?' he said.

'Well, in the generality of things I'd say it's hard to tell, given that it's hard to find evidence of crimes not committed,' said the hangman, giving the trapdoor a final rattle. 'But in the specificality, sir, I'd say it's very efficacious.'

'Meaning what?' said Moist.

'Meaning I've never seen someone up here more'n once, sir. Shall we go?'

There was a stir when they climbed up into the chilly morning air, followed by a few boos and even some applause. People were strange like that. Steal five dollars and you were a petty thief. Steal thousands of dollars and you were either a government or a hero.

Moist stared ahead while the roll call of his crimes was read out. He couldn't help feeling that it was so unfair. He'd never so much as tapped someone on the head. He'd never even broken down a door. He had picked locks on occasion, but he'd always locked them again behind him. Apart from all those repossessions, bankruptcies and sudden insolvencies, what had he actually done that was bad, as such? He'd only been moving numbers around.

'Nice crowd turned out today,' said Mr Trooper, tossing the end of the rope over the beam and busying himself with knots. 'Lot of press, too. What Gallows? covers 'em all, o' course, and there's the Times and the Pseudopolis Herald, prob'ly because of that bank what collapsed there, and I heard there's a man from the Sto Plains Dealer, too. Very good financial section - I always keep an eye on the used rope prices. Looks like a lot of people want to see you dead, sir.'

Moist was aware that a black coach had drawn up at the rear of the crowd. There was no coat of arms on the door, unless you were in on the secret, which was that Lord Vetinari's coat of arms featured a sable shield. Black on black. You had to admit that the bastard had style-

'Huh? What?' he said, in response to a nudge.

'I asked if you have any last words, Mr Spangler?' said the hangman. 'It's customary. I wonder if you might have thought of any?'

'I wasn't actually expecting to die,' said Moist. And that was it. He really hadn't, until now. He'd been certain that something would turn up.

'Good one, sir,' said Mr Wilkinson. 'We'll go with that, shall we?'

Moist narrowed his eyes. The curtain on a coach window had twitched. The coach door had opened. Hope, that greatest of all treasures, ventured a little glitter.

'No, they're not my actual last words,' he said. 'Er . . . let me think . . .' A slight, clerk-like figure was descending from the coach.

'Er . . . it's not as bad a thing I do now . . . er . . .' Aha, it all made some kind of sense now. Vetinari was out to scare him, that was it. That would be just like the man, from what Moist had heard. There was going to be a reprieve!

'I . . . er . . . I . . .'

Down below, the clerk was having difficulty getting through the press of people. 'Do you mind speeding up a bit, Mr Spangler?' said the hangman. 'Fair's fair, eh?'

'I want to get it right,' said Moist haughtily, watching the clerk negotiate his way around a large troll.

'Yes, but there's a limit, sir,' said the hangman, annoyed at this breach of etiquette. 'Otherwise you could go ah, er, um for days! Short and sweet, sir, that's the style.'

'Right, right,' said Spangler. 'Er . . . oh, look, see that man there? Waving at you?'

The hangman glanced down at the clerk, who'd struggled to the front of the crowd.

'I bring a message from Lord Vetinari!' the man shouted.

'Right!' said Moist.

'He says to get on with it, it's long past dawn!' said the clerk.

'Oh,' said Moist, staring at the black coach. That damn Vetinari had a warder's sense of humour, too.

'Come on, Mr Spangler, you don't want me to get into trouble, do you?' said the hangman, patting him on the shoulder. 'Just a few words, and then we can all get on with our lives. Present company excepted, obviously.'

So this was it. It was, in some strange way, rather liberating. You didn't have to fear the worst that could happen any more, because this was it, and it was nearly over. The warder had been right. What you had to do in this life was get past the pineapple, Moist told himself. It was big and sharp and knobbly, but there might be peaches underneath. It was a myth to live by and so, right now, totally useless.

'In that case,' said Moist von Lipwig, 'I commend my soul to any god that can find it.'

'Nice,' said the hangman, and pulled the lever.

Albert Spangler died.

It was generally agreed that they had been good last words.

'Ah, Mr Lipwig,' said a distant voice, getting closer. 'I see you are awake. And still alive, at the present time.'

There was a slight inflection to that last phrase which told Moist that the length of the present time was entirely in the gift of the speaker.

He opened his eyes. He was sitting in a comfortable chair. At a desk opposite him, sitting with his hands steepled reflectively in front of his pursed lips, was Havelock, Lord Vetinari, under whose idiosyncratically despotic rule Ankh-Morpork had become the city where, for some reason, everyone wanted to live. An ancient animal sense also told Moist that other people were standing behind the comfortable chair, and that it could be extremely uncomfortable should he make any sudden movements. But they couldn't be as terrible as the thin, black-robed man with the fussy little beard and the pianist's hands who was watching him.

'Shall I tell you about angels, Mr Lipwig?' said the Patrician pleasantly. 'I know two interesting facts about them.'

Moist grunted. There were no obvious escape routes in front of him, and turning round was out of the question. His neck ached horribly.

'Oh, yes. You were hanged,' said Vetinari. 'A very precise science, hanging. Mr Trooper is a master. The slippage and thickness of the rope, whether the knot is placed here rather than there, the relationship between weight and distance . . . oh, I'm sure the man could write a book. You were hanged to within half an inch of your life, I understand. Only an expert standing right next to you would have spotted that, and in this case the expert was our friend Mr Trooper. No, Albert Spangler is dead, Mr Lipwig. Three hundred people would swear they saw him die.' He leaned forward. 'And so, appropriately, it is of angels I wish to talk to you now.'

Moist managed a grunt.

'The first interesting thing about angels, Mr Lipwig, is that sometimes, very rarely, at a point in a man's career where he has made such a foul and tangled mess of his life that death appears to be the only sensible option, an angel appears to him, or, I should say, unto him, and offers him a chance to go back to the moment when it all went wrong, and this time do it right. Mr Lipwig, I should like you to think of me as . . . an angel.'

Moist stared. He'd felt the snap of the rope, the choke of the noose! He'd seen the blackness welling up! He'd died!

'I'm offering you a job, Mr Lipwig. Albert Spangler is buried, but Mr Lipwig has a future. It may, of course, be a very short one, if he is stupid. I am offering you a job, Mr Lipwig. Work, for wages. I realize the concept may not be familiar.'

Only as a form of hell, Moist thought.

'The job is that of Postmaster General of the Ankh-Morpork Post Office.'

Moist continued to stare.

'May I just add, Mr Lipwig, that behind you there is a door. If at any time in this interview you feel you wish to leave, you have only to step through it and you will never hear from me again.'

Moist filed that under 'deeply suspicious'.

'To continue: the job, Mr Lipwig, involves the refurbishment and running of the city's postal service, preparation of the international packets, maintenance of Post Office property, et cetera, et cetera-'

'If you stick a broom up my arse I could probably sweep the floor, too,' said a voice. Moist realized it was his. His brain was a mess. It had come as a shock to find that the afterlife is this one.

Lord Vetinari gave him a long, long look.

'Well, if you wish,' he said, and turned to a hovering clerk. 'Drumknott, does the housekeeper have a store cupboard on this floor, do you know?'

'Oh, yes, my lord,' said the clerk. 'Shall I-'

'It was a joke!' Moist burst out.

'Oh, I'm sorry, I hadn't realized,' said Lord Vetinari, turning back to Moist. 'Do tell me if you feel obliged to make another one, will you?'

'Look,' said Moist, 'I don't know what's happening here, but I don't know anything about delivering post!'

'Mr Moist, this morning you had no experience at all of being dead, and yet but for my intervention you would nevertheless have turned out to be extremely good at it,' said Lord Vetinari sharply. 'It just goes to show: you never know until you try.'

'But when you sentenced me-'

Vetinari raised a pale hand. 'Ah?' he said.

Moist's brain, at last aware that it needed to do some work here, stepped in and replied: 'Er . . . when you . . . sentenced . . . Albert Spangler-'

'Well done. Do carry on.'

'-you said he was a natural born criminal, a fraudster by vocation, an habitual liar, a perverted genius and totally untrustworthy!'

'Are you accepting my offer, Mr Lipwig?' said Vetinari sharply.

Moist looked at him. 'Excuse me,' he said, standing up, 'I'd just like to check something.'

There were two men dressed in black standing behind his chair. It wasn't a particularly neat black, more the black worn by people who just don't want little marks to show. They looked like clerks, until you met their eyes. They stood aside as Moist walked towards the door which, as promised, was indeed there. He opened it very carefully. There was nothing beyond, and that included a floor. In the manner of one who is going to try all possibilities, he took the remnant of spoon out of his pocket and let it drop. It was quite a long time before he heard the jingle.

Then he went back and sat in the chair.

'The prospect of freedom?' he said.

'Exactly,' said Lord Vetinari. 'There is always a choice.'

'You mean . . . I could choose certain death?'

'A choice, nevertheless,' said Vetinari. 'Or, perhaps, an alternative. You see, I believe in freedom, Mr Lipwig. Not many people do, although they will of course protest otherwise. And no practical definition of freedom would be complete without the freedom to take the consequences. Indeed, it is the freedom upon which all the others are based. Now . . . will you take the job? No one will recognize you, I am sure. No one ever recognizes you, it would appear.'

Moist shrugged. 'Oh, all right. Of course, I accept as natural born criminal, habitual liar, fraudster and totally untrustworthy perverted genius.'

'Capital! Welcome to government service!' said Lord Vetinari, extending his hand. 'I pride myself on being able to pick the right man. The wage is twenty dollars a week and, I believe, the Postmaster General has the use of a small apartment in the main building. I think there's a hat, too. I shall require regular reports. Good day.'

He looked down at his paperwork. He looked up.

'You appear to be still here, Postmaster General?'

'And that's it?' said Moist, aghast. 'One minute I'm being hanged, next minute you're employing me?'

'Let me see . . . yes, I think so. Oh, no. Of course. Drumknott, do give Mr Lipwig his keys.'

The clerk stepped forward and handed Moist a huge, rusted keyring full of keys, and proffered a clipboard. 'Sign here, please, Postmaster General,' he said. Hold on a minute, Moist thought, this is only one city. It's got gates. It's completely surrounded by different directions to run. Does it matter what I sign?

'Certainly,' he said, and scribbled his name.

'Your correct name, if you please,' said Lord Vetinari, not looking up from his desk. 'What name did he sign, Drumknott?'

The clerk craned his head. 'Er . . . Ethel Snake, my lord, as far as I can make out.'

'Do try to concentrate, Mr Lipwig,' said Vetinari wearily, still apparently reading the paperwork.

Moist signed again. After all, what would it matter in the long run? And it would certainly be a long run, if he couldn't find a horse.

'And that leaves only the matter of your parole officer,' said Lord Vetinari, still engrossed in the paper before him.

'Parole officer?'

'Yes. I'm not completely stupid, Mr Lipwig. He will meet you outside the Post Office building in ten minutes. Good day.'

When Moist had left, Drumknott coughed politely and said, 'Do you think he'll turn up there, my lord?'

'One must always consider the psychology of the individual,' said Vetinari, correcting the spelling on an official report. 'That is what I do all the time and lamentably, Drumknott, you do not always do. That is why he has walked off with your pencil.'

Always move fast. You never know what's catching you up.

Ten minutes later Moist von Lipwig was well outside the city. He'd bought a horse, which was a bit embarrassing, but speed had been of the essence and he'd only had time to grab one of his emergency stashes from its secret hiding place and pick up a skinny old screw from the Bargain Box in Hobson's Livery Stable. At least it'd mean no irate citizen going to the Watch.

No one had bothered him. No one had looked at him twice; no one ever did. The city gates had indeed been wide open. The plains lay ahead of him, full of opportunity. And he was good at parlaying nothing into something. For example, at the first little town he came to he'd go to work on this old nag with a few simple techniques and ingredients that'd make it worth twice the price he'd paid for it, at least for about twenty minutes or until it rained. Twenty minutes would be enough time to sell it and, with any luck, pick up a better horse worth slightly more than the asking price. He'd do it again at the next town and in three days, maybe four, he'd have a horse worth owning.

But that would be just a sideshow, something to keep his hand in. He'd got three very nearly diamond rings sewn into the lining of his coat, a real one in a secret pocket in the sleeve, and a very nearly gold dollar stitched cunningly into the collar. These were, to him, what his saw and hammer are to a carpenter. They were primitive tools, but they'd put him back in the game.

There is a saying 'You can't fool an honest man' which is much quoted by people who make a profitable living by fooling honest men. Moist never knowingly tried it, anyway. If you did fool an honest man, he tended to complain to the local Watch, and these days they were harder to buy off. Fooling dishonest men was a lot safer and, somehow, more sporting. And, of course, there were so many more of them. You hardly had to aim.

Half an hour after arriving in the town of Hapley, where the big city was a tower of smoke on the horizon, he was sitting outside an inn, downcast, with nothing in the world but a genuine diamond ring worth a hundred dollars and a pressing need to get home to Genua, where his poor aged mother was dying of Gnats. Eleven minutes later he was standing patiently outside a jeweller's shop, inside which the jeweller was telling a sympathetic citizen that the ring the stranger was prepared to sell for twenty dollars was worth seventy-five (even jewellers have to make a living). And thirty-five minutes after that he was riding out on a better horse, with five dollars in his pocket, leaving behind a gloating sympathetic citizen who, despite having been bright enough to watch Moist's hands carefully, was about to go back to the jeweller to try to sell for seventy-five dollars a shiny brass ring with a glass stone that was worth fifty pence of anybody's money.

The world was blessedly free of honest men, and wonderfully full of people who believed they could tell the difference between an honest man and a crook. He tapped his jacket pocket. The jailers had taken the map off him, of course, probably while he was busy being a dead man. It was a good map, and in studying it Mr Wilkinson and his chums would learn a lot about decryption, geography and devious cartography. They wouldn't find in it the whereabouts of AM$150,000 in mixed currencies, though, because the map was a complete and complex fiction. However, Moist entertained a wonderful warm feeling inside to think that they would, for some time, possess that greatest of all treasures, which is Hope. Anyone who couldn't simply remember where he'd stashed a great big fortune deserved to lose it, in Moist's opinion. But, for now, he'd have to keep away from it, while having it to look forward to . . .

Moist didn't even bother to note the name of the next town. It had an inn, and that was enough. He took a room with a view over a disused alley, checked that the window opened easily, ate an adequate meal, and had an early night. Not bad at all, he thought. This morning he'd been on the scaffold with the actual noose round his actual neck, tonight he was back in business. All he need do now was grow a beard again, and keep away from Ankh-Morpork for six months. Or perhaps only three.

Moist had a talent. He'd also acquired a lot of skills so completely that they were second nature. He'd learned to be personable, but something in his genetics made him unmemorable. He had the talent of not being noticed, for being a face in the crowd. People had difficulty describing him. He was . . . he was 'about'. He was about twenty, or about thirty. On Watch reports across the continent he was anywhere between, oh, about six feet two inches and five feet nine inches tall, hair all shades from mid-brown to blond, and his lack of distinguishing features included his entire face. He was about . . . average. What people remembered was the furniture, things like spectacles and moustaches, so he always carried a selection of both. They remembered names and mannerisms, too. He had hundreds of those.

Oh, and they reme

- Home

- Fiction

- Action & Adventure

- Going Postal

Going Postal

SIZE GUIDE

- ISBN: 9780857525086

- Author: Terry Pratchett

- Publisher: Doubleday Book

- Pages: 496

- Format: Hardback

Book Description

A beautiful new hardback edition of the classic Discworld novel.

Moist von Lipwig is a con artist and a fraud and a man faced with a life choice: be hanged, or put Ankh-Morpork's ailing postal service back on its feet.

It was a tough decision.

But he's got to see that the mail gets though, come rain, hail, sleet, dogs, the Post Office Workers Friendly and Benevolent Society, the evil chairman of the Grand Trunk Semaphore Company, and a midnight killer.

Getting a date with Adora Bell Dearheart would be nice, too.

Review

'Like many of Pratchett's best comic novels, it is a book about redemption ... There's a moral toughness here, which is one of the reasons why Pratchett is never merely frivolous.' - Time Out

'With all the puns, strange names and quick-fire jokes about captive letters demanding to be delivered, it's easy to miss how cross about injustice Terry Pratchett can be. This darkness and concrete morality sets his work apart from imitators of his English Absurd school of comic fantasy.' - Guardian

'Terry Pratchett is one of the great makers of what Auden called 'secondary worlds'. His inventiveness - with people with plots, with things - is seemingly inexhaustible ... Pratchett can make you giggle helplessly and then grin grimly at the sharpness of his wit. Twelve-year old boys love him, but he himself is grown up. He knows that terrible things exist and happen, and he invents a benign otherworld in which we can face them, and laugh.' - A.S. Byatt, DAILY MAIL

'Pratchett ... is the missing link between Douglas Adams and J.K. Rowling. To non-initiates his work is gobbledygook, but dig deeper and you find the wit and imaginationthat have gained him a fanatical readership - among them is A.S. Byatt.' - FT MAGAZINE

About the Author

Terry Pratchett was the acclaimed creator of the global bestselling Discworld series, the first of which, The Colour of Magic, was published in 1983. In all, he was the author of over fifty bestselling books which have sold over 100 million copies worldwide. His novels have been widely adapted for stage and screen, and he was the winner of multiple prizes, including the Carnegie Medal. He was awarded a knighthood for services to literature in 2009, although he always wryly maintained that his greatest service to literature was to avoid writing any.

www.terrypratchettbooks.com

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Angel

In which our Hero experiences Hope, the Greatest Gift — The Bacon Sandwich of Regret — Sombre Reflections on Capital Punishment from the Hangman — Famous Last Words — Our Hero Dies — Angels, conversations about — Inadvisability of Misplaced Offers regarding Broomsticks — An Unexpected Ride — A World Free of Honest Men — A Man on the Hop — There is Always a Choice

They say that the prospect of being hanged in the morning concentrates a man's mind wonderfully; unfortunately, what the mind inevitably concentrates on is that it is in a body that, in the morning, is going to be hanged.

The man going to be hanged had been named Moist von Lipwig by doting if unwise parents, but he was not going to embarrass the name, in so far as that was still possible, by being hung under it. To the world in general, and particularly on that bit of it known as the death warrant, he was Albert Spangler.

And he took a more positive approach to the situation and had concentrated his mind on the prospect of not being hanged in the morning, and most particularly on the prospect of removing all the crumbling mortar from around a stone in his cell wall with a spoon. So far the work had taken him five weeks, and reduced the spoon to something like a nail file. Fortunately, no one ever came to change the bedding here, or else they would have discovered the world's heaviest mattress. It was the large and heavy stone that was currently the object of his attentions, and at some point a huge staple had been hammered into it as an anchor for manacles.

Moist sat down facing the wall, gripped the iron ring in both hands, braced his legs against the stones on either side, and heaved.

His shoulders caught fire and a red mist filled his vision but the block slid out, with a faint and inappropriate tinkling noise. Moist managed to ease it away from the hole and peered inside.

At the far end was another block, and the mortar around it looked suspiciously strong and fresh.

Just in front of it was a new spoon. It was shiny.

As he studied it, he heard the clapping behind him. He turned his head, tendons twanging a little riff of agony, and saw several of the warders watching him through the bars.

'Well done, Mr Spangler!' said one of them. 'Ron here owes me five dollars! I told him you were a sticker! He's a sticker, I said!'

'You set this up, did you, Mr Wilkinson?' said Moist weakly, watching the glint of light on the spoon.

'Oh, not us, sir. Lord Vetinari's orders. He insists that all condemned prisoners should be offered the prospect of freedom.'

'Freedom? But there's a damn great stone through there!'

'Yes, there is that, sir, yes, there is that,' said the warder. 'It's only the prospect, you see. Not actual free freedom as such. Hah, that'd be a bit daft, eh?'

'I suppose so, yes,' said Moist. He didn't say 'you bastards.' The warders had treated him quite civilly this past six weeks, and he made a point of getting on with people. He was very, very good at it. People skills were part of his stock-in-trade; they were nearly the whole of it. Besides, these people had big sticks. So, speaking carefully, he added: 'Some people might consider this cruel, Mr Wilkinson.'

'Yes, sir, we asked him about that, sir, but he said no, it wasn't. He said it provided-' his forehead wrinkled '-occ-you-pay-shun-all ther-rap-py, healthy exercise, prevented moping and offered that greatest of all treasures which is Hope, sir.'

'Hope,' muttered Moist glumly.

'Not upset, are you, sir?'

'Upset? Why should I be upset, Mr Wilkinson?'

'Only the last bloke we had in this cell, he managed to get down that drain, sir. Very small man. Very agile.'

Moist looked at the little grid in the floor. He'd dismissed it out of hand. 'Does it lead to the river?' he said.

The warder grinned. 'You'd think so, wouldn't you? He was really upset when we fished him out. Nice to see you've entered into the spirit of the thing, sir. You've been an example to all of us, sir, the way you kept going. Stuffing all the dust in your mattress? Very clever, very tidy. Very neat. It's really cheered us up, having you in here. By the way, Mrs Wilkinson says ta very much for the fruit basket. Very posh, it is. It's got kumquats, even!'

'Don't mention it, Mr Wilkinson.'

'The Warden was a bit green about the kumquats 'cos he only got dates in his, but I told him, sir, that fruit baskets is like life: until you've got the pineapple off'f the top you never know what's underneath. He says thank you, too.'

'Glad he liked it, Mr Wilkinson,' said Moist absent-mindedly. Several of his former landladies had brought in presents for 'the poor confused boy', and Moist always invested in generosity. A career like his was all about style, after all.

'On that general subject, sir,' said Mr Wilkinson, 'me and the lads were wondering if you might like to unburden yourself, at this point in time, on the subject of the whereabouts of the place where the location of the spot is where, not to beat about the bush, you hid all that money you stole . . .?'

The jail went silent. Even the cockroaches were listening.

'No, I couldn't do that, Mr Wilkinson,' said Moist loudly, after a decent pause for dramatic effect. He tapped his jacket pocket, held up a finger and winked. The warders grinned back.

'We understand totally, sir. Now I'd get some rest if I was you, sir, 'cos we're hanging you in half an hour,' said Mr Wilkinson.

'Hey, don't I get breakfast?'

'Breakfast isn't until seven o'clock, sir,' said the warder reproachfully. 'But, tell you what, I'll do you a bacon sandwich. 'cos it's you, Mr Spangler.'

***

And now it was a few minutes before dawn and it was him being led down the short corridor and out into the little room under the scaffold. Moist realized he was looking at himself from a distance, as if part of himself was floating outside his body like a child's balloon ready, as it were, for him to let go of the string.

The room was lit by light coming through cracks in the scaffold floor above, and significantly from around the edges of the large trapdoor. The hinges of said door were being carefully oiled by a man in a hood.

He stopped when he saw the party arrive and said, 'Good morning, Mr Spangler.' He raised the hood helpfully. 'It's me, sir, Daniel "One Drop" Trooper. I am your executioner for today, sir. Don't you worry, sir. I've hanged dozens of people. We'll soon have you out of here.'

'Is it true that if a man isn't hanged after three attempts he's reprieved, Dan?' said Moist, as the executioner carefully wiped his hands on a rag.

'So I've heard, sir, so I've heard. But they don't call me One Drop for nothing, sir. And will sir be having the black bag today?'

'Will it help?'

'Some people think it makes them look more dashing, sir. And it stops that pop-eyed look. It's more a crowd thing, really. Quite a big one out there this morning. Nice piece about you in the Times yesterday, I thought. All them people saying what a nice young man you were, and everything. Er . . . would you mind signing the rope beforehand, sir? I mean, I won't have a chance to ask you afterwards, eh?'

'Signing the rope?' said Moist.

'Yessir,' said the hangman. 'It's sort of traditional. There's a lot of people out there who buy old rope. Specialist collectors, you could say. A bit strange, but it takes all sorts, eh? Worth more signed, of course.' He flourished a length of stout rope. 'I've got a special pen that signs on rope. One signature every couple of inches? Straightforward signature, no dedication needed. Worth money to me, sir. I'd be very grateful.'

'So grateful that you won't hang me, then?' said Moist, taking the pen. This got an appreciative laugh. Mr Trooper watched him sign along the length, nodding happily.

'Well done, sir, that's my pension plan you're signing there. Now . . . are we ready, everyone?'

'Not me!' said Moist quickly, to another round of general amusement.

'You're a card, Mr Spangler,' said Mr Wilkinson. 'It won't be the same without you around, and that's the truth.'

'Not for me, at any rate,' said Moist. This was, once again, treated like rapier wit. Moist sighed. 'Do you really think all this deters crime, Mr Trooper?' he said.

'Well, in the generality of things I'd say it's hard to tell, given that it's hard to find evidence of crimes not committed,' said the hangman, giving the trapdoor a final rattle. 'But in the specificality, sir, I'd say it's very efficacious.'

'Meaning what?' said Moist.

'Meaning I've never seen someone up here more'n once, sir. Shall we go?'

There was a stir when they climbed up into the chilly morning air, followed by a few boos and even some applause. People were strange like that. Steal five dollars and you were a petty thief. Steal thousands of dollars and you were either a government or a hero.

Moist stared ahead while the roll call of his crimes was read out. He couldn't help feeling that it was so unfair. He'd never so much as tapped someone on the head. He'd never even broken down a door. He had picked locks on occasion, but he'd always locked them again behind him. Apart from all those repossessions, bankruptcies and sudden insolvencies, what had he actually done that was bad, as such? He'd only been moving numbers around.

'Nice crowd turned out today,' said Mr Trooper, tossing the end of the rope over the beam and busying himself with knots. 'Lot of press, too. What Gallows? covers 'em all, o' course, and there's the Times and the Pseudopolis Herald, prob'ly because of that bank what collapsed there, and I heard there's a man from the Sto Plains Dealer, too. Very good financial section - I always keep an eye on the used rope prices. Looks like a lot of people want to see you dead, sir.'

Moist was aware that a black coach had drawn up at the rear of the crowd. There was no coat of arms on the door, unless you were in on the secret, which was that Lord Vetinari's coat of arms featured a sable shield. Black on black. You had to admit that the bastard had style-

'Huh? What?' he said, in response to a nudge.

'I asked if you have any last words, Mr Spangler?' said the hangman. 'It's customary. I wonder if you might have thought of any?'

'I wasn't actually expecting to die,' said Moist. And that was it. He really hadn't, until now. He'd been certain that something would turn up.

'Good one, sir,' said Mr Wilkinson. 'We'll go with that, shall we?'

Moist narrowed his eyes. The curtain on a coach window had twitched. The coach door had opened. Hope, that greatest of all treasures, ventured a little glitter.

'No, they're not my actual last words,' he said. 'Er . . . let me think . . .' A slight, clerk-like figure was descending from the coach.

'Er . . . it's not as bad a thing I do now . . . er . . .' Aha, it all made some kind of sense now. Vetinari was out to scare him, that was it. That would be just like the man, from what Moist had heard. There was going to be a reprieve!

'I . . . er . . . I . . .'

Down below, the clerk was having difficulty getting through the press of people. 'Do you mind speeding up a bit, Mr Spangler?' said the hangman. 'Fair's fair, eh?'

'I want to get it right,' said Moist haughtily, watching the clerk negotiate his way around a large troll.

'Yes, but there's a limit, sir,' said the hangman, annoyed at this breach of etiquette. 'Otherwise you could go ah, er, um for days! Short and sweet, sir, that's the style.'

'Right, right,' said Spangler. 'Er . . . oh, look, see that man there? Waving at you?'

The hangman glanced down at the clerk, who'd struggled to the front of the crowd.

'I bring a message from Lord Vetinari!' the man shouted.

'Right!' said Moist.

'He says to get on with it, it's long past dawn!' said the clerk.

'Oh,' said Moist, staring at the black coach. That damn Vetinari had a warder's sense of humour, too.

'Come on, Mr Spangler, you don't want me to get into trouble, do you?' said the hangman, patting him on the shoulder. 'Just a few words, and then we can all get on with our lives. Present company excepted, obviously.'

So this was it. It was, in some strange way, rather liberating. You didn't have to fear the worst that could happen any more, because this was it, and it was nearly over. The warder had been right. What you had to do in this life was get past the pineapple, Moist told himself. It was big and sharp and knobbly, but there might be peaches underneath. It was a myth to live by and so, right now, totally useless.

'In that case,' said Moist von Lipwig, 'I commend my soul to any god that can find it.'

'Nice,' said the hangman, and pulled the lever.

Albert Spangler died.

It was generally agreed that they had been good last words.

'Ah, Mr Lipwig,' said a distant voice, getting closer. 'I see you are awake. And still alive, at the present time.'

There was a slight inflection to that last phrase which told Moist that the length of the present time was entirely in the gift of the speaker.

He opened his eyes. He was sitting in a comfortable chair. At a desk opposite him, sitting with his hands steepled reflectively in front of his pursed lips, was Havelock, Lord Vetinari, under whose idiosyncratically despotic rule Ankh-Morpork had become the city where, for some reason, everyone wanted to live. An ancient animal sense also told Moist that other people were standing behind the comfortable chair, and that it could be extremely uncomfortable should he make any sudden movements. But they couldn't be as terrible as the thin, black-robed man with the fussy little beard and the pianist's hands who was watching him.

'Shall I tell you about angels, Mr Lipwig?' said the Patrician pleasantly. 'I know two interesting facts about them.'

Moist grunted. There were no obvious escape routes in front of him, and turning round was out of the question. His neck ached horribly.

'Oh, yes. You were hanged,' said Vetinari. 'A very precise science, hanging. Mr Trooper is a master. The slippage and thickness of the rope, whether the knot is placed here rather than there, the relationship between weight and distance . . . oh, I'm sure the man could write a book. You were hanged to within half an inch of your life, I understand. Only an expert standing right next to you would have spotted that, and in this case the expert was our friend Mr Trooper. No, Albert Spangler is dead, Mr Lipwig. Three hundred people would swear they saw him die.' He leaned forward. 'And so, appropriately, it is of angels I wish to talk to you now.'

Moist managed a grunt.

'The first interesting thing about angels, Mr Lipwig, is that sometimes, very rarely, at a point in a man's career where he has made such a foul and tangled mess of his life that death appears to be the only sensible option, an angel appears to him, or, I should say, unto him, and offers him a chance to go back to the moment when it all went wrong, and this time do it right. Mr Lipwig, I should like you to think of me as . . . an angel.'

Moist stared. He'd felt the snap of the rope, the choke of the noose! He'd seen the blackness welling up! He'd died!

'I'm offering you a job, Mr Lipwig. Albert Spangler is buried, but Mr Lipwig has a future. It may, of course, be a very short one, if he is stupid. I am offering you a job, Mr Lipwig. Work, for wages. I realize the concept may not be familiar.'

Only as a form of hell, Moist thought.

'The job is that of Postmaster General of the Ankh-Morpork Post Office.'

Moist continued to stare.

'May I just add, Mr Lipwig, that behind you there is a door. If at any time in this interview you feel you wish to leave, you have only to step through it and you will never hear from me again.'

Moist filed that under 'deeply suspicious'.

'To continue: the job, Mr Lipwig, involves the refurbishment and running of the city's postal service, preparation of the international packets, maintenance of Post Office property, et cetera, et cetera-'

'If you stick a broom up my arse I could probably sweep the floor, too,' said a voice. Moist realized it was his. His brain was a mess. It had come as a shock to find that the afterlife is this one.

Lord Vetinari gave him a long, long look.

'Well, if you wish,' he said, and turned to a hovering clerk. 'Drumknott, does the housekeeper have a store cupboard on this floor, do you know?'

'Oh, yes, my lord,' said the clerk. 'Shall I-'

'It was a joke!' Moist burst out.

'Oh, I'm sorry, I hadn't realized,' said Lord Vetinari, turning back to Moist. 'Do tell me if you feel obliged to make another one, will you?'

'Look,' said Moist, 'I don't know what's happening here, but I don't know anything about delivering post!'

'Mr Moist, this morning you had no experience at all of being dead, and yet but for my intervention you would nevertheless have turned out to be extremely good at it,' said Lord Vetinari sharply. 'It just goes to show: you never know until you try.'

'But when you sentenced me-'

Vetinari raised a pale hand. 'Ah?' he said.

Moist's brain, at last aware that it needed to do some work here, stepped in and replied: 'Er . . . when you . . . sentenced . . . Albert Spangler-'

'Well done. Do carry on.'

'-you said he was a natural born criminal, a fraudster by vocation, an habitual liar, a perverted genius and totally untrustworthy!'

'Are you accepting my offer, Mr Lipwig?' said Vetinari sharply.

Moist looked at him. 'Excuse me,' he said, standing up, 'I'd just like to check something.'

There were two men dressed in black standing behind his chair. It wasn't a particularly neat black, more the black worn by people who just don't want little marks to show. They looked like clerks, until you met their eyes. They stood aside as Moist walked towards the door which, as promised, was indeed there. He opened it very carefully. There was nothing beyond, and that included a floor. In the manner of one who is going to try all possibilities, he took the remnant of spoon out of his pocket and let it drop. It was quite a long time before he heard the jingle.

Then he went back and sat in the chair.

'The prospect of freedom?' he said.

'Exactly,' said Lord Vetinari. 'There is always a choice.'

'You mean . . . I could choose certain death?'

'A choice, nevertheless,' said Vetinari. 'Or, perhaps, an alternative. You see, I believe in freedom, Mr Lipwig. Not many people do, although they will of course protest otherwise. And no practical definition of freedom would be complete without the freedom to take the consequences. Indeed, it is the freedom upon which all the others are based. Now . . . will you take the job? No one will recognize you, I am sure. No one ever recognizes you, it would appear.'

Moist shrugged. 'Oh, all right. Of course, I accept as natural born criminal, habitual liar, fraudster and totally untrustworthy perverted genius.'

'Capital! Welcome to government service!' said Lord Vetinari, extending his hand. 'I pride myself on being able to pick the right man. The wage is twenty dollars a week and, I believe, the Postmaster General has the use of a small apartment in the main building. I think there's a hat, too. I shall require regular reports. Good day.'

He looked down at his paperwork. He looked up.

'You appear to be still here, Postmaster General?'

'And that's it?' said Moist, aghast. 'One minute I'm being hanged, next minute you're employing me?'

'Let me see . . . yes, I think so. Oh, no. Of course. Drumknott, do give Mr Lipwig his keys.'

The clerk stepped forward and handed Moist a huge, rusted keyring full of keys, and proffered a clipboard. 'Sign here, please, Postmaster General,' he said. Hold on a minute, Moist thought, this is only one city. It's got gates. It's completely surrounded by different directions to run. Does it matter what I sign?

'Certainly,' he said, and scribbled his name.

'Your correct name, if you please,' said Lord Vetinari, not looking up from his desk. 'What name did he sign, Drumknott?'

The clerk craned his head. 'Er . . . Ethel Snake, my lord, as far as I can make out.'

'Do try to concentrate, Mr Lipwig,' said Vetinari wearily, still apparently reading the paperwork.

Moist signed again. After all, what would it matter in the long run? And it would certainly be a long run, if he couldn't find a horse.

'And that leaves only the matter of your parole officer,' said Lord Vetinari, still engrossed in the paper before him.

'Parole officer?'

'Yes. I'm not completely stupid, Mr Lipwig. He will meet you outside the Post Office building in ten minutes. Good day.'

When Moist had left, Drumknott coughed politely and said, 'Do you think he'll turn up there, my lord?'

'One must always consider the psychology of the individual,' said Vetinari, correcting the spelling on an official report. 'That is what I do all the time and lamentably, Drumknott, you do not always do. That is why he has walked off with your pencil.'

Always move fast. You never know what's catching you up.

Ten minutes later Moist von Lipwig was well outside the city. He'd bought a horse, which was a bit embarrassing, but speed had been of the essence and he'd only had time to grab one of his emergency stashes from its secret hiding place and pick up a skinny old screw from the Bargain Box in Hobson's Livery Stable. At least it'd mean no irate citizen going to the Watch.

No one had bothered him. No one had looked at him twice; no one ever did. The city gates had indeed been wide open. The plains lay ahead of him, full of opportunity. And he was good at parlaying nothing into something. For example, at the first little town he came to he'd go to work on this old nag with a few simple techniques and ingredients that'd make it worth twice the price he'd paid for it, at least for about twenty minutes or until it rained. Twenty minutes would be enough time to sell it and, with any luck, pick up a better horse worth slightly more than the asking price. He'd do it again at the next town and in three days, maybe four, he'd have a horse worth owning.

But that would be just a sideshow, something to keep his hand in. He'd got three very nearly diamond rings sewn into the lining of his coat, a real one in a secret pocket in the sleeve, and a very nearly gold dollar stitched cunningly into the collar. These were, to him, what his saw and hammer are to a carpenter. They were primitive tools, but they'd put him back in the game.

There is a saying 'You can't fool an honest man' which is much quoted by people who make a profitable living by fooling honest men. Moist never knowingly tried it, anyway. If you did fool an honest man, he tended to complain to the local Watch, and these days they were harder to buy off. Fooling dishonest men was a lot safer and, somehow, more sporting. And, of course, there were so many more of them. You hardly had to aim.

Half an hour after arriving in the town of Hapley, where the big city was a tower of smoke on the horizon, he was sitting outside an inn, downcast, with nothing in the world but a genuine diamond ring worth a hundred dollars and a pressing need to get home to Genua, where his poor aged mother was dying of Gnats. Eleven minutes later he was standing patiently outside a jeweller's shop, inside which the jeweller was telling a sympathetic citizen that the ring the stranger was prepared to sell for twenty dollars was worth seventy-five (even jewellers have to make a living). And thirty-five minutes after that he was riding out on a better horse, with five dollars in his pocket, leaving behind a gloating sympathetic citizen who, despite having been bright enough to watch Moist's hands carefully, was about to go back to the jeweller to try to sell for seventy-five dollars a shiny brass ring with a glass stone that was worth fifty pence of anybody's money.

The world was blessedly free of honest men, and wonderfully full of people who believed they could tell the difference between an honest man and a crook. He tapped his jacket pocket. The jailers had taken the map off him, of course, probably while he was busy being a dead man. It was a good map, and in studying it Mr Wilkinson and his chums would learn a lot about decryption, geography and devious cartography. They wouldn't find in it the whereabouts of AM$150,000 in mixed currencies, though, because the map was a complete and complex fiction. However, Moist entertained a wonderful warm feeling inside to think that they would, for some time, possess that greatest of all treasures, which is Hope. Anyone who couldn't simply remember where he'd stashed a great big fortune deserved to lose it, in Moist's opinion. But, for now, he'd have to keep away from it, while having it to look forward to . . .

Moist didn't even bother to note the name of the next town. It had an inn, and that was enough. He took a room with a view over a disused alley, checked that the window opened easily, ate an adequate meal, and had an early night. Not bad at all, he thought. This morning he'd been on the scaffold with the actual noose round his actual neck, tonight he was back in business. All he need do now was grow a beard again, and keep away from Ankh-Morpork for six months. Or perhaps only three.

Moist had a talent. He'd also acquired a lot of skills so completely that they were second nature. He'd learned to be personable, but something in his genetics made him unmemorable. He had the talent of not being noticed, for being a face in the crowd. People had difficulty describing him. He was . . . he was 'about'. He was about twenty, or about thirty. On Watch reports across the continent he was anywhere between, oh, about six feet two inches and five feet nine inches tall, hair all shades from mid-brown to blond, and his lack of distinguishing features included his entire face. He was about . . . average. What people remembered was the furniture, things like spectacles and moustaches, so he always carried a selection of both. They remembered names and mannerisms, too. He had hundreds of those.

Oh, and they reme

User reviews

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to get Email Updates!

Thanks for subscribing.

Your response has been recorded.

India's Iconic & Independent Book Store offering a vast selection of books across a variety of genres Since 1978.

"We Believe In The Power of Books" Our mission is to make books accessible to everyone, and to cultivate a culture of reading and learning. We strive to provide a wide range of books, from classic literature, sci-fi and fantasy, to graphic novels, biographies and self-help books, so that everyone can find something to read.

Whether you’re looking for your next great read, a gift for someone special, or just browsing, Midland is here to make your book-buying experience easy and enjoyable.

We are shipping pan India and across the world.

For Bulk Order / Corporate Gifting

+91 9818282497 |

+91 9818282497 |  [email protected]

[email protected]

Click To Know More

INFORMATION

QUICK LINKS

ADDRESS

Shop No.20, Aurobindo Palace Market, Near Church, New Delhi