- Contemporary Fiction

- Contemporary Fiction

- Children

- Children

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Non-Fiction

- Non-Fiction

- Fiction

- Fiction

Secularism emerged in 17thcentury Europe as an essential element of what became the modern state. The separation of church and state that it entailed paved the way for the democratic republics we take for granted today. Tolerance, as understood in the West, was sought to be introduced as state policy by the British in India too. But our nationalist leaders understood their country better than to adopt the concept without local adjustments.

Political philosopher Nalini Rajan examines the tension between religious freedom and state intervention in India, a tension that comes with the idea of ‘principled’ state intervention in matters of religion, as mandated by the Constitution. Demands for reservations and separate electorates by minorities in the early twentieth century had essentially ruled out absolute state neutrality in this respect. But it is only by analysing the fascinating debates on secularism in the Constituent Assembly (1946–49) that we see how and why the specific provisions on minority rights—Articles 25 to 30—came to be adopted. These provisions implicitly envisioned a key role for the judiciary. A full section of this book is thus devoted to understanding the role that the courts have played in establishing, and just as importantly, defining Indian secularism—through such judgements as in the Shirur Mutt case of 1954, the Durgah Committee case of 1961, the Satsangi case of 1966, the Stanislaus case of 1977, the Shah

Secularism How India Reshaped The Idea

SIZE GUIDE

- ISBN: 9789354476716

- Author: Nalini Rajan

- Publisher: Speaking Tiger

- Pages: 136

- Format: Paperback

Book Description

Secularism emerged in 17thcentury Europe as an essential element of what became the modern state. The separation of church and state that it entailed paved the way for the democratic republics we take for granted today. Tolerance, as understood in the West, was sought to be introduced as state policy by the British in India too. But our nationalist leaders understood their country better than to adopt the concept without local adjustments.

Political philosopher Nalini Rajan examines the tension between religious freedom and state intervention in India, a tension that comes with the idea of ‘principled’ state intervention in matters of religion, as mandated by the Constitution. Demands for reservations and separate electorates by minorities in the early twentieth century had essentially ruled out absolute state neutrality in this respect. But it is only by analysing the fascinating debates on secularism in the Constituent Assembly (1946–49) that we see how and why the specific provisions on minority rights—Articles 25 to 30—came to be adopted. These provisions implicitly envisioned a key role for the judiciary. A full section of this book is thus devoted to understanding the role that the courts have played in establishing, and just as importantly, defining Indian secularism—through such judgements as in the Shirur Mutt case of 1954, the Durgah Committee case of 1961, the Satsangi case of 1966, the Stanislaus case of 1977, the Shah

User reviews

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to get Email Updates!

Thanks for subscribing.

Your response has been recorded.

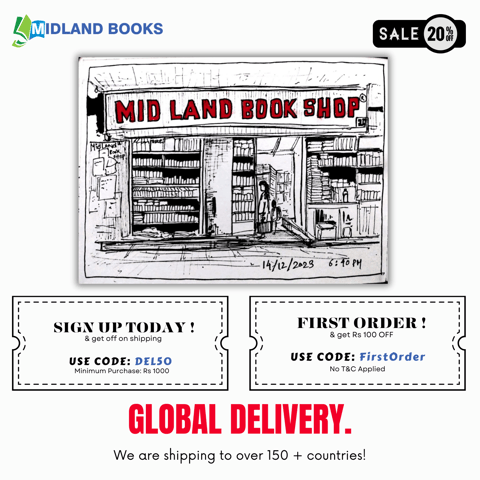

India's Iconic & Independent Book Store offering a vast selection of books across a variety of genres Since 1978.

"We Believe In The Power of Books" Our mission is to make books accessible to everyone, and to cultivate a culture of reading and learning. We strive to provide a wide range of books, from classic literature, sci-fi and fantasy, to graphic novels, biographies and self-help books, so that everyone can find something to read.

Whether you’re looking for your next great read, a gift for someone special, or just browsing, Midland is here to make your book-buying experience easy and enjoyable.

We are shipping pan India and across the world.

For Bulk Order / Corporate Gifting

+91 9818282497 |

+91 9818282497 |  [email protected]

[email protected]

Click To Know More

INFORMATION

QUICK LINKS

ADDRESS

Shop No.20, Aurobindo Palace Market, Near Church, New Delhi