- Contemporary Fiction

- Contemporary Fiction

- Children

- Children

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Non-Fiction

- Non-Fiction

- Fiction

- Fiction

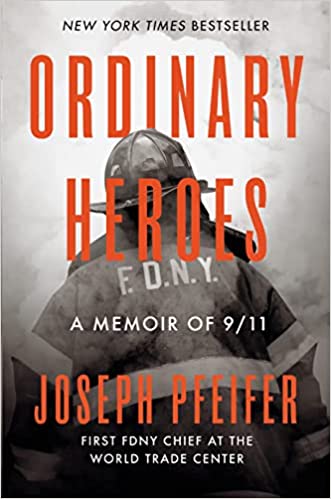

From the first FDNY chief to respond to the 9/11 attacks, an intimate memoir and a tribute to those who died that others might live

When Chief Joe Pfeifer led his firefighters to investigate an odor of gas in downtown Manhattan on the morning of 9/11, he had no idea that his life was about to change forever. A few moments later, he watched as the first plane crashed into the World Trade Center. Pfeifer, the closest FDNY chief to the scene, spearheaded rescue efforts on one of the darkest days in American history.

Ordinary Heroes is the unforgettable and intimate account of what Chief Pfeifer witnessed at Ground Zero, on that day and the days that followed. Through his eyes, we see the horror of the attack and the courage of the firefighters who ran into the burning towers to save others. We see him send his own brother up the stairs of the North Tower, never to return. And we walk with him and his fellow firefighters through weeks of rescue efforts and months of numbing grief, as they wrestle with the real meaning of heroism and leadership.

This gripping narrative gives way to resiliency and a determination that permanently reshapes Pfeifer, his fellow firefighters, NYC, and America. Ordinary Heroes takes us on a journey that turns traumatic memories into hope, so we can make good on our promise to never forget 9/11.

Review

"Pfeifer’s record of that day and its aftermath surely enters the canon as one of the necessary documents of 9/11. But it’s his inclusive sense of public service, one that values the heroism of those who do ordinary things in extraordinary times, that makes Ordinary Heroes a book for today.”—The New York Times

“With great humility, Chief Pfeifer has crafted a moving story of how the FDNY was anything but ordinary in the aftermath of the worst terrorist attack this country has ever seen. An incredible picture of the resilience, humor, and heart of New York’s bravest.”—Jon Stewart

“A heartfelt, affecting book that sheds new light on one of the darkest moments in recent history.”—Kirkus Reviews

“I responded to the World Trade Center attacks along with Chief Joseph Pfeifer. His memoir of that day takes me back to those horrific events in a way no other book about 9/11 has done. A vivid, compelling, and accurate portrayal of the gut-wrenching experiences of the FDNY’s fire chiefs and firefighters that morning, both inside and outside the Twin Towers.”—Salvatore Cassano, former FDNY fire commissioner and chief of department

“A deeply personal and emotionally charged recollection of unthinkable events. Some people go their whole lives and they’re never really tested. Chief Pfeifer was tested, as were so many that day and he was proven a true hero.”—Susan Zirinsky, former president, CBS News; senior executive producer, CBS News Content Studio; and co-executive producer, 9/11

“One of my many pleasures of doing interviews for my NYC Epicenter documentary was meeting my brother FDNY Chief Joe Pfeifer. He is a son of New York City, who rose through the ranks to deal with NYC’s most severe events in his stellar thirty-seven-year career at the FDNY. This book is a living testament to the ‘Bravest,’ to the greatest fire department in the whole world.”—Spike Lee

“A powerful look at an unforgettable event. After experiencing the loss of hundreds of firefighters, Chief Pfeifer became an advocate for change in the first-responder community that inspired interagency collaboration. His book provides a rare look behind the curtain at the everyday heroes and their courage, pain, and perseverance.”—Cathy L. Lanier, former chief of the Metropolitan Police Department, Washington, D.C.

“Joe Pfeifer’s courage, leadership, and team-building skills are beyond reproach, and Ordinary Heroes is an essential narrative about the importance of those skills in a time of crisis.”—John Abizaid, former commander, U.S. Central Command, and ambassador to Saudi Arabia

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

2. Aiming for the North Tower

At 8:33 a.m., we got the call to respond to a “possible odor of gas” about seven blocks north of the firehouse. Firefighters gulped the last of their breakfast coffee and grabbed their helmets and bunker gear. Guys still upstairs slid down the firehouse pole.

Nobody got excited. It was a routine emergency, one of the most common calls to the firehouse. Each person goes to his designated spot on the apparatus.

Captain Dennis Tardio and his firefighters hopped on the Engine, which carries hose, nozzles and connections to standpipes. He was joined by Chauffeur Tom Spinard, who had the important responsibility of correctly positioning the Engine at hydrants when we arrived at a fire scene, making sure that the water pressure was maintained. Firefighters Jamal Braithwaite, Joe Casaliggi and Pat Zoda took their usual spots on the rig.

Lt. Bill Walsh did the same with the Ladder, or Truck, which carries the various tools we used to force entry or to check for fire spread. Chauffeur John O’Neill took his designated seat, as Firefighters Nick Borillo, Damian Van Cleaf, Steve Olsen and Hank Ryan climbed into their seats.

Jules, who had started riding along with me on most shifts in the battalion chief’s vehicle jumped into the back seat of my red Suburban with a rack of flashing lights. Gedeon was usually the one who did the filming, while Jules assisted him with logistics. But Gedeon had urged Jules to learn how to shoot as well, and in August, they had bought a second camera. That morning, Jules rode with me to practice filming for one more run before heading home after the long night.

The FDNY dispatcher sent us to the northeast corner of Church and Lispenard Streets in Tribeca. We’d meet two more rigs at the scene. We were responding with two Engines, two Ladders, and a battalion chief, a typical response for an odor of gas because of the fear of an explosion.

Arriving in three minutes, we dismounted the rigs into a glorious September morning: pristine blue sky, bright sun, mild temperature, summer just heading into fall, one of those “top ten” days of the year that makes you feel alive, ready to tackle anything.

Standing in the street, I pulled out a gas detector about the size of a firefighter’s portable radio with a very sensitive probe on the top, which I carried in my vehicle. After a few minutes walking up and down the street, I got a buzzing sound, a hit, over a sewer grate, and a whiff of sewer gas, a normal false positive. I sent some firefighters into basements and nearby restaurants, looking for the source, and they found none. As was standard practice, I asked my aide to contact Con Ed to check it out with their equipment.

Suddenly, I heard the thunderous roar of jet engines at full throttle. In Manhattan, you rarely hear planes because of the tall buildings. Looking west, I saw a low-flying commercial airliner so close that I could read the word “American” on the fuselage. Racing south above the Hudson River, visible just above the buildings on Church Street, the plane zoomed past us and disappeared from my sight for a couple of seconds behind some taller buildings.

When it reappeared, I saw the aircraft was aiming at the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

It was 8:46 a.m.

I stood on the street and watched as the airplane crumpled into the World Trade Center. The aircraft slammed dead center into the building, the wings carving a huge gash through the upper floors of the 110-story skyscraper. A massive fireball erupted, followed a second later by an ear-splitting explosion. Black smoke billowed from the wound the aircraft had ripped in the steel and glass building.

The impact took my breath away. Time seemed to stand still as we watched the flames. Then the firefighters around me erupted with a chorus of “Holy shit! Oh, my God! Holy shit! A plane hit the building!”

In horror and disbelief, I tried to comprehend what I had just seen. One of the tallest buildings in the world was on fire. Thousands of people were in that building or arriving to begin their workday. We were only a few blocks from the World Trade Center, almost certainly some of the closest firefighters to the disaster. As the closest chief in lower Manhattan, I knew instantly I was going to be the first chief on the scene and would have to take command.

“Get back on the rigs!” shouted Captain Tardio to Engine 7’s firefighters, who grabbed their equipment, and scrambled into their places on the vehicles. Lt. Walsh did the same thing with the firefighters of Ladder 1.

I jumped back into my red SUV, followed by Jules. “Go, go to the Trade Center,” I told firefighter Ed Fahey, who that day was driving me for the first time as a battalion aide. His job was to drive with lights and sirens, so I could talk on the department radio.

I looked up at the smoking North Tower and grabbed the radio. I needed to give concise orders to command and control our response.

“Battalion 1 to Manhattan.”

“Battalion 1,” the dispatcher responded.

“We just had a plane crash into upper floors of the World Trade Center,” I said. “Transmit a second alarm and start relocating companies into the area.”

“Ten-four Battalion 1.”

“Battalion 1 is also sending the whole assignment on this box to that area.” I was informing the dispatcher the units with me at the odor of gas were now assigned to the WTC. “This box” was referring to the location of the red fire callbox on the corner. All the rigs on that box were now heading to Box 8087, the North Tower of the WTC.

With lights flashing and sirens blaring, our convoy raced south on West Broadway to the WTC.

Adrenalin pumping, in seconds my mind flooded with a hundred pieces of information as I thought about my next moves. Fighting thousands of fires had taught me how to recognize danger, and to enhance my senses to pick up small bits of information and process them at lightning speed.

“That was an American Airlines plane,” I said. “That looked like a direct attack.” I tried to comprehend what had taken place. I had no idea who was responsible, but I knew it was a terrorist attack. I could feel my heart rate subtly increase.

At the height of the workday, there were as many as 40,000 people in the WTC complex. Hundreds of people had probably died as the plane bulldozed through the building. Many others were likely in danger. Of one thing, I was certain: We were going to the biggest fire of our lifetime, the biggest fire since the FDNY was founded in 1865. I was in charge of the FDNY response for now. I had to gather situational awareness, inform the dispatcher, request additional alarms, develop a plan and deploy firefighting resources.

As we drove, I watched white and black smoke billowing from the building. After the initial fireball, I saw no more flame. It was difficult to identify exactly which floors were involved, but certainly, multiple floors were now internally ablaze, and the fire would quickly spread.

Over the years as a firefighter, I had learned how important it was in a crisis to be flexible in my thought processes. I learned when to rely on intuitive gut feelings—that wall is about to collapse! Get out!—and when to switch to deliberate or analytical thinking. Especially as a chief, being able to step back and see the big picture is crucial.

I forced myself into a deliberate calm. Though I had extensive experience with high-rise fires and taught the subject at the fire academy, none of us had ever been confronted with a massive high-rise fire on numerous upper floors. My focus was: what do I need to do right now?

Sixty seconds after giving the first radio transmission, I got on the radio again.

“Battalion 1 to Manhattan . . . We have a number of floors on fire. It looked like the plane was aiming towards the building. Transmit a third alarm. We’ll have the staging area at Vesey and West Street. Have the third alarm assignment go into that area, the second alarm assignment to report to the building.”

The dispatcher and the incoming units needed to know what I knew in my gut: this was not an accident but a deliberate attack by a plane aiming for the building.

- Home

- Non-Fiction

- Ordinary Heroes A Memoir Of 9/11

Ordinary Heroes A Memoir Of 9/11

SIZE GUIDE

- ISBN: 9780593330258

- Author: Joseph Pfeifer

- Publisher: Penguin Portfolio

- Pages: 256

- Format: Hardback

Book Description

From the first FDNY chief to respond to the 9/11 attacks, an intimate memoir and a tribute to those who died that others might live

When Chief Joe Pfeifer led his firefighters to investigate an odor of gas in downtown Manhattan on the morning of 9/11, he had no idea that his life was about to change forever. A few moments later, he watched as the first plane crashed into the World Trade Center. Pfeifer, the closest FDNY chief to the scene, spearheaded rescue efforts on one of the darkest days in American history.

Ordinary Heroes is the unforgettable and intimate account of what Chief Pfeifer witnessed at Ground Zero, on that day and the days that followed. Through his eyes, we see the horror of the attack and the courage of the firefighters who ran into the burning towers to save others. We see him send his own brother up the stairs of the North Tower, never to return. And we walk with him and his fellow firefighters through weeks of rescue efforts and months of numbing grief, as they wrestle with the real meaning of heroism and leadership.

This gripping narrative gives way to resiliency and a determination that permanently reshapes Pfeifer, his fellow firefighters, NYC, and America. Ordinary Heroes takes us on a journey that turns traumatic memories into hope, so we can make good on our promise to never forget 9/11.

Review

"Pfeifer’s record of that day and its aftermath surely enters the canon as one of the necessary documents of 9/11. But it’s his inclusive sense of public service, one that values the heroism of those who do ordinary things in extraordinary times, that makes Ordinary Heroes a book for today.”—The New York Times

“With great humility, Chief Pfeifer has crafted a moving story of how the FDNY was anything but ordinary in the aftermath of the worst terrorist attack this country has ever seen. An incredible picture of the resilience, humor, and heart of New York’s bravest.”—Jon Stewart

“A heartfelt, affecting book that sheds new light on one of the darkest moments in recent history.”—Kirkus Reviews

“I responded to the World Trade Center attacks along with Chief Joseph Pfeifer. His memoir of that day takes me back to those horrific events in a way no other book about 9/11 has done. A vivid, compelling, and accurate portrayal of the gut-wrenching experiences of the FDNY’s fire chiefs and firefighters that morning, both inside and outside the Twin Towers.”—Salvatore Cassano, former FDNY fire commissioner and chief of department

“A deeply personal and emotionally charged recollection of unthinkable events. Some people go their whole lives and they’re never really tested. Chief Pfeifer was tested, as were so many that day and he was proven a true hero.”—Susan Zirinsky, former president, CBS News; senior executive producer, CBS News Content Studio; and co-executive producer, 9/11

“One of my many pleasures of doing interviews for my NYC Epicenter documentary was meeting my brother FDNY Chief Joe Pfeifer. He is a son of New York City, who rose through the ranks to deal with NYC’s most severe events in his stellar thirty-seven-year career at the FDNY. This book is a living testament to the ‘Bravest,’ to the greatest fire department in the whole world.”—Spike Lee

“A powerful look at an unforgettable event. After experiencing the loss of hundreds of firefighters, Chief Pfeifer became an advocate for change in the first-responder community that inspired interagency collaboration. His book provides a rare look behind the curtain at the everyday heroes and their courage, pain, and perseverance.”—Cathy L. Lanier, former chief of the Metropolitan Police Department, Washington, D.C.

“Joe Pfeifer’s courage, leadership, and team-building skills are beyond reproach, and Ordinary Heroes is an essential narrative about the importance of those skills in a time of crisis.”—John Abizaid, former commander, U.S. Central Command, and ambassador to Saudi Arabia

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

2. Aiming for the North Tower

At 8:33 a.m., we got the call to respond to a “possible odor of gas” about seven blocks north of the firehouse. Firefighters gulped the last of their breakfast coffee and grabbed their helmets and bunker gear. Guys still upstairs slid down the firehouse pole.

Nobody got excited. It was a routine emergency, one of the most common calls to the firehouse. Each person goes to his designated spot on the apparatus.

Captain Dennis Tardio and his firefighters hopped on the Engine, which carries hose, nozzles and connections to standpipes. He was joined by Chauffeur Tom Spinard, who had the important responsibility of correctly positioning the Engine at hydrants when we arrived at a fire scene, making sure that the water pressure was maintained. Firefighters Jamal Braithwaite, Joe Casaliggi and Pat Zoda took their usual spots on the rig.

Lt. Bill Walsh did the same with the Ladder, or Truck, which carries the various tools we used to force entry or to check for fire spread. Chauffeur John O’Neill took his designated seat, as Firefighters Nick Borillo, Damian Van Cleaf, Steve Olsen and Hank Ryan climbed into their seats.

Jules, who had started riding along with me on most shifts in the battalion chief’s vehicle jumped into the back seat of my red Suburban with a rack of flashing lights. Gedeon was usually the one who did the filming, while Jules assisted him with logistics. But Gedeon had urged Jules to learn how to shoot as well, and in August, they had bought a second camera. That morning, Jules rode with me to practice filming for one more run before heading home after the long night.

The FDNY dispatcher sent us to the northeast corner of Church and Lispenard Streets in Tribeca. We’d meet two more rigs at the scene. We were responding with two Engines, two Ladders, and a battalion chief, a typical response for an odor of gas because of the fear of an explosion.

Arriving in three minutes, we dismounted the rigs into a glorious September morning: pristine blue sky, bright sun, mild temperature, summer just heading into fall, one of those “top ten” days of the year that makes you feel alive, ready to tackle anything.

Standing in the street, I pulled out a gas detector about the size of a firefighter’s portable radio with a very sensitive probe on the top, which I carried in my vehicle. After a few minutes walking up and down the street, I got a buzzing sound, a hit, over a sewer grate, and a whiff of sewer gas, a normal false positive. I sent some firefighters into basements and nearby restaurants, looking for the source, and they found none. As was standard practice, I asked my aide to contact Con Ed to check it out with their equipment.

Suddenly, I heard the thunderous roar of jet engines at full throttle. In Manhattan, you rarely hear planes because of the tall buildings. Looking west, I saw a low-flying commercial airliner so close that I could read the word “American” on the fuselage. Racing south above the Hudson River, visible just above the buildings on Church Street, the plane zoomed past us and disappeared from my sight for a couple of seconds behind some taller buildings.

When it reappeared, I saw the aircraft was aiming at the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

It was 8:46 a.m.

I stood on the street and watched as the airplane crumpled into the World Trade Center. The aircraft slammed dead center into the building, the wings carving a huge gash through the upper floors of the 110-story skyscraper. A massive fireball erupted, followed a second later by an ear-splitting explosion. Black smoke billowed from the wound the aircraft had ripped in the steel and glass building.

The impact took my breath away. Time seemed to stand still as we watched the flames. Then the firefighters around me erupted with a chorus of “Holy shit! Oh, my God! Holy shit! A plane hit the building!”

In horror and disbelief, I tried to comprehend what I had just seen. One of the tallest buildings in the world was on fire. Thousands of people were in that building or arriving to begin their workday. We were only a few blocks from the World Trade Center, almost certainly some of the closest firefighters to the disaster. As the closest chief in lower Manhattan, I knew instantly I was going to be the first chief on the scene and would have to take command.

“Get back on the rigs!” shouted Captain Tardio to Engine 7’s firefighters, who grabbed their equipment, and scrambled into their places on the vehicles. Lt. Walsh did the same thing with the firefighters of Ladder 1.

I jumped back into my red SUV, followed by Jules. “Go, go to the Trade Center,” I told firefighter Ed Fahey, who that day was driving me for the first time as a battalion aide. His job was to drive with lights and sirens, so I could talk on the department radio.

I looked up at the smoking North Tower and grabbed the radio. I needed to give concise orders to command and control our response.

“Battalion 1 to Manhattan.”

“Battalion 1,” the dispatcher responded.

“We just had a plane crash into upper floors of the World Trade Center,” I said. “Transmit a second alarm and start relocating companies into the area.”

“Ten-four Battalion 1.”

“Battalion 1 is also sending the whole assignment on this box to that area.” I was informing the dispatcher the units with me at the odor of gas were now assigned to the WTC. “This box” was referring to the location of the red fire callbox on the corner. All the rigs on that box were now heading to Box 8087, the North Tower of the WTC.

With lights flashing and sirens blaring, our convoy raced south on West Broadway to the WTC.

Adrenalin pumping, in seconds my mind flooded with a hundred pieces of information as I thought about my next moves. Fighting thousands of fires had taught me how to recognize danger, and to enhance my senses to pick up small bits of information and process them at lightning speed.

“That was an American Airlines plane,” I said. “That looked like a direct attack.” I tried to comprehend what had taken place. I had no idea who was responsible, but I knew it was a terrorist attack. I could feel my heart rate subtly increase.

At the height of the workday, there were as many as 40,000 people in the WTC complex. Hundreds of people had probably died as the plane bulldozed through the building. Many others were likely in danger. Of one thing, I was certain: We were going to the biggest fire of our lifetime, the biggest fire since the FDNY was founded in 1865. I was in charge of the FDNY response for now. I had to gather situational awareness, inform the dispatcher, request additional alarms, develop a plan and deploy firefighting resources.

As we drove, I watched white and black smoke billowing from the building. After the initial fireball, I saw no more flame. It was difficult to identify exactly which floors were involved, but certainly, multiple floors were now internally ablaze, and the fire would quickly spread.

Over the years as a firefighter, I had learned how important it was in a crisis to be flexible in my thought processes. I learned when to rely on intuitive gut feelings—that wall is about to collapse! Get out!—and when to switch to deliberate or analytical thinking. Especially as a chief, being able to step back and see the big picture is crucial.

I forced myself into a deliberate calm. Though I had extensive experience with high-rise fires and taught the subject at the fire academy, none of us had ever been confronted with a massive high-rise fire on numerous upper floors. My focus was: what do I need to do right now?

Sixty seconds after giving the first radio transmission, I got on the radio again.

“Battalion 1 to Manhattan . . . We have a number of floors on fire. It looked like the plane was aiming towards the building. Transmit a third alarm. We’ll have the staging area at Vesey and West Street. Have the third alarm assignment go into that area, the second alarm assignment to report to the building.”

The dispatcher and the incoming units needed to know what I knew in my gut: this was not an accident but a deliberate attack by a plane aiming for the building.

User reviews

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to get Email Updates!

Thanks for subscribing.

Your response has been recorded.

India's Iconic & Independent Book Store offering a vast selection of books across a variety of genres Since 1978.

"We Believe In The Power of Books" Our mission is to make books accessible to everyone, and to cultivate a culture of reading and learning. We strive to provide a wide range of books, from classic literature, sci-fi and fantasy, to graphic novels, biographies and self-help books, so that everyone can find something to read.

Whether you’re looking for your next great read, a gift for someone special, or just browsing, Midland is here to make your book-buying experience easy and enjoyable.

We are shipping pan India and across the world.

For Bulk Order / Corporate Gifting

+91 9818282497 |

+91 9818282497 |  [email protected]

[email protected]

Click To Know More

INFORMATION

ACCOUNT

TRACK SHIPMENT

ADDRESS

Shop No.20, Aurobindo Palace Market, Near Church, New Delhi