-

Non-ficton

- Non-ficton

-

Contemporary Fiction

- Contemporary Fiction

-

Children

- Children

-

Comics & Graphic Novels

- Comics & Graphic Novels

-

Non-Fiction

- Non-Fiction

-

Fiction

- Fiction

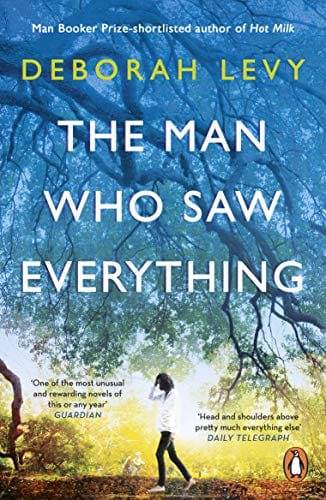

LONGLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2019

SHORTLISTED FOR THE GOLDSMITHS PRIZE 2019

'An ice-cold skewering of patriarchy, humanity and the darkness of 20th century Europe' The Times

_________________________________

'It's like this, Saul Adler.'

'No, it's like this, Jennifer Moreau.'

In 1988, Saul Adler is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. Apparently fine, he gets up and poses for a photograph taken by his girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau. He carries this photo with him to East Berlin: a fragment of the present, an anchor to the West.

But in the GDR he finds himself troubled by time - stalked by the spectres of history, slipping in and out of a future that does not yet exist. Until, in 2016, Saul attempts to cross the Abbey Road again . . .

_________________________________

'A time-bending, location-hopping tale of love, truth and the power of seeing. Thoroughly gripping' Sunday Telegraph

'Writing so beautiful it stops the reader on the page' Independent

'Levy splices time in artfully believable, mesmerizing strokes' Lambda Literary

'Skewering totalitarianism - from the state, to the family, to the strictures of the male gaze - Levy explodes conventional narrative to explore the individual's place and culpability within history' Guardian

'An utterly beguiling fever dream' Daily Telegraph

From the Inside Flap

In 1989 Saul Adler ( a narcissistic, young historian) is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. He is apparently fine; he gets up and goes to see his art student girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau . They have sex then break up, but not before she has photographed Saul crossing the same Abbey Road. Saul leaves to study in communist East Berlin, two months before the Wall comes down. There he will encounter - significantly - both his assigned translator and his translator's sister, who swears she has seen a jaguar prowling the city. He will fall in love and brood upon his difficult, authoritarian father. And he will befriend a hippy, Rainer, who may or may not be a Stasi agent, but will certainly return to haunt him in middle age.

In 2016, Saul Adler is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. He is rushed to hospital, where he spends the following days slipping in and out of consciousness, and in and out of memories of the past. A number of people gather at his bedside. One of them is Jennifer Moreau. But someone important is missing.

Slipping slyly between time zones and leaving a spiralling trail, Deborah Levy's electrifying The Man Who Saw Everything examines what we see and what we fail to see, the grave crime of carelessness, the weight of history and our ruinous attempts to shrug it off.

--This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition.Review

“Deborah Levy's prose is light-handed and leaves a pleasant sting … in the new novel, Levy looks at masculinity through the point of view of Saul, a proud defector who sneers at 'authoritarian old men' like his father and the regimes they create, their dependence on walls, imaginative and real.” -Parul Sehgal, The New York Times

“Levy, as evidenced in Hot Milk (2016) and Swimming Home (2011), is a master of the seemingly loose yet actually taut story... As in her previous books, Levy's prose in The Man Who Saw Everything is controlled, refractive, sharply intelligent. There's no wasted motion. Single sentences render character with the clarity, and cruelty, of a snapshot...Love is unsettling, Levy suggests, and so is time, and so is sexuality, and so is the self. The Man Who Saw Everything, in its ghostly play of personal and political histories, bears witness to this truth.” -The Boston Globe

“In one short and sly book after another, [Levy] writes about characters navigating swerves of history and sexuality, and the social and personal rootlessness that accompanies both. If the themes sound weighty, Levy's elliptical fiction is the opposite, thanks in part to her wry appreciation of dramatic ironies at work. Her restless protagonists travel the Continent trying to forge an identity, only to discover that history has a way of laying traps for us-and also offering escapes when we least anticipate them. The Man Who Saw Everything, Levy's most stylistically complex novel yet. ... Levy's boldness, and her voice, are hard earned. ... Levy doesn't whisper in her fiction, but in her slim, elliptical books, she unspools big odysseys.” -The Atlantic

“Elliptical, elusive and endlessly stimulating… The Man Who Saw Everything is a brilliantly constructed jigsaw puzzle of meaning that will leave readers wondering how much they can ever truly know.” -The Washington Post

“Deborah Levy's novels are small masterworks of inlay, meticulously constructed. And The Man Who Saw Everything is perhaps her cleverest. But cleverness for its own sake is clearly not what interests her. Being human does. That is mystery enough, she repeatedly proves, as she tantalizes us with connections and secrets that seem to hover at the edge of our vision. Few writers, for example, can summon sadness with such force…Big ideas thud onto the page, like apples hitting the roof of that garden shed, but we hardly hear them. Deborah Levy makes us listen instead for the fragile rhythm of a breaking heart.” -Wall Street Journal

“Haunting and effective…Irresistible.” -Associated Press

“A work of philosophy and art... Each novel Man Booker finalist Deborah Levy writes comes nearer perfection.” -New York Journal of Books

“Deborah Levy, one of the most intellectually exciting writers in Britain today, has produced in this perplexing work a caustically funny exploration of history, perception, the nature of political tyranny and how lovers can simultaneously charm and erase each other.” -New York Times Book Review

“Levy's writing is playful, smart, and full of memorable lines.” -NPR.org

“Levy's deceivingly slim books are crammed with allusions to her literary progenitors: Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, but also Louise Bourgeois, Claude Chaun, and Cindy Sherman. For Levy is, above all, a visual writer, heaping image upon tantalizing image… Her novels are meticulously structured. They circle in on themselves, full of repetitions, allusions, and elisions whose logic unfailingly reveals itself at the end. With Levy, you are never quite sure of your footing. But she is… he experience of reading her is much like the jolt and pleasure of being submerged in water-resurfacing to find that the weather has turned.” -The New York Review of Books

“Longtime readers of Levy's work will know that she's just as capable of voyaging into the surreal and uncanny as she is documenting the social and psychological mores of her characters… you have a sense of a writer who's capable of nearly anything… a writer whose work has crossed boundaries of format and genre.” -Longreads

“Reading Deborah Levy's novels is a lesson in humility. She is a careful and intelligent writer with an absolute command of language, one who demands you not only to pay close attention, but also second-guess your immediate reactions and responses to her work. Her novels are deceptively slim in length, but supersized with profound ideas that defy preconceived notions and easy interpretations. The Man Who Saw Everything is just such a book, and reading it is the best possible sort of challenge” -Newsday

“A superbly crafted, enigmatic new story from an author of note…In a relatively short book, Levy spins an extraordinary web of connection, a dreamscape in which plangent images like a pearl necklace, a spilled drink, or the petals of a tree recur like soft chimes…Head-spinning and playful yet translucent, Levy's writing offers sophistication and delightful artistry. Levy defies gravity in a daring, time-bending new novel.” -Starred Review, Kirkus Reviews

“Booker Prize–finalist Levy (Hot Milk) explores the fragile connections and often vast chasms between self and others in this playful, destabilizing, and consistently surprising novel… Levy's novel brilliantly explores the parallels between personal and political history, and prompts questions about how one sees oneself-and what others see.” -Starred Review, Publishers Weekly

“The Man Who Saw Everything is bifurcated into two time periods: 1988 and 2016, but by Deborah Levy's deft hand and brilliant command of metaphor, the boundaries of space and time collapse. This is an extraordinary novel that captures the zeitgeist and specters of 20th-century Communism in such a way that far exceeds the 200 pages it is bound in.” -Shelf Awareness

“Audacious… compelling … the book [has] an understated power, as we confront a writer working against expectation to subvert the conventions of the novel, to rethink the form on her own terms.” -New Republic

“An evocative journey across a shape-shifting personal and political landscape. As Levy peels back each new layer of this at-times enigmatic story, there are new pleasures disclosed at every turn.” -Bookpage

“There is no way to succinctly summarize this slim book and adequately convey how it manages to hold exquisitely actual multiverses within its pages… A brilliant, blistering, bold look at identity, relationships, and time; a perfect puzzle of a novel.” -Nylon

“[An] utterly beguiling fever dream of a novel, which revisits aspects of Europe's authoritarian 20th-century history through the delirium of one man's shattered mind… Nominated for this year's Booker Prize, The Man Who Saw Everything is an intricate jigsaw, full of pieces that tantalizingly never quite fit together. . . In writing that is as clear as a stream yet also full of withheld meaning, Levy suggests that the grief and guilt inside Saul . . . is connected to Europe's legacy of persecution, paranoia, and totalitarianism.” -Daily Telegraph

“Deborah Levy's intelligent and supple latest novel, The Man Who Saw Everything, recently longlisted for the Booker Prize… is stunningly disorienting, fascinating . . . the balance shifts through Levy's skillful, dizzying storytelling.” -The Financial Times

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

‘I apologize,’ he said. ‘You walked on to the crossing and I slowed down, preparing to stop, but then you changed your mind and walked back to the kerb.’ His eyelids were quivering at the corners. ‘And then without warning you lurched forward on to the crossing.’ I smiled at his careful reconstruction of history, blatantly told in his favour. He furtively glanced at his car to check if it had been damaged. The wing mirror had shattered. His thin lips parted and hesighed sorrowfully, muttering something about how he had ordered the mirror from Milan. I had been up all night writing a lecture on the psychology of male tyrants and I’d made a start with the way Stalin flirted with women by flicking bread at them across the dinner table. My notes, about five sheets of paper, had fallen out of my leather sling bag and, embarrassingly, so had a packet of condoms. I started to pick them up. A small, flat, rectangular object was lying in the road. I noticed the driver was looking at my knuckles as I handed him the object, which felt warm and seemed to be vibrating in my palm. It was not mine soI assumed it was his. Blood dripped through my fingers. My palms were grazed and there was a cut on the knuckle of my left hand. I sucked it while he watched me, clearly distressed.

‘Do you need a lift somewhere?’

‘I’m okay.’

He offered to take me to a pharmacy to ‘clean up the wound’, as he put it. When I shook my head, he reached out his hand and touched my hair, which was strangely comforting. He asked for my name.

‘Saul Adler. Look, it’s just a small graze. I have thin skin. I always bleed a lot, it’s nothing.’

He was holding his left arm in a strange way, cradling it with his right arm. I picked up the condoms and shoved them into my jacket pocket. A wind was up. The leaves that had been swept into small piles under the trees were blowing across the road. The driver told me the traffic had been diverted because there was a demonstration that day in London, and he’d wondered if Abbey Road was closed off. The detour was not signposted clearly. He did not understand why he’d become confused, because he often came this way to watch the cricket at Lord’s, nearby. While he spoke, he gazed at the rectangular object in his hand.

The object was speaking. There was definitely a voice inside it, a man’s voice, and he was saying something angry and insulting. We both pretended not to hear his words.

Fuck off I hate you don’t come home

‘How old are you, Soorl? Can you tell me where you live?

’I think the near collision had really scared the driver.

When I told him I was twenty-eight, he didn’t believe me and asked for my age again. He was so posh he pronounced my name as if a pebble had been inserted between the roof of his mouth and his lower lip. His silver hair was slicked back with a product that made it shine.

I in turn asked for his name.

‘Wolfgang,’ he said very quickly, as if he did not want me toremember it.

‘Like Mozart,’ I said, and then, rather like a child showing his father where he’d been hurt after falling off a swing, I pointed to the cut on my knuckle and kept repeating that I was okay. His concerned tone was starting to make me tearful. I wanted him to drive off and leave me alone. Perhaps the tears were to do with my father’s recent death, though my father was not as groomed or as gentle as shiny, silver-haired Wolfgang. To hasten his departure, I explained that my girlfriend was about to arrive any minute now, so he didn’t have to hang around. In fact she was going to take a photograph of me stepping on to the zebra crossing in the style of the photograph on the Beatles album.

‘Which album is that, Soorl?’

‘It’s called Abbey Road. Everyone knows that. Where have youbeen, Wolfgang?’

He laughed but he looked sad. Perhaps it was because of the insultingwords that had been spoken from inside the vibrating object in his hand.

‘And how old is your girlfriend?’

‘Twenty-three. Actually, Abbey Road was the last album the Beatles recorded together at the EMI studios, which are just over there.’ I pointed to a large white house on the other side of the road.

‘Of course, I know that,’ he said sadly. ‘It’s nearly as famous as Buckingham Palace.’ He walked back to his car, murmuring, ‘Take care, Soorl. You’re lucky to have such a young girlfriend. By the way, what do you do?’

His comments and questions were starting to irritate me – also the way he sighed, as if he carried the weight of the world on the shoulders of his beige cashmere coat. I decided not to reveal that I was a historian and that my subject was communist Eastern Europe.

It was a relief to hear the animal growl of his engine revving as I stepped back on the pavement. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

- Home

- Fiction

- Historical Fiction

- The Man Who Saw Everything

The Man Who Saw Everything

SIZE GUIDE

- ISBN: 9780241977606

- Author: Deborah Levy

- Publisher: Penguin

- Pages: 204

- Format: Paperback

Book Description

LONGLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE 2019

SHORTLISTED FOR THE GOLDSMITHS PRIZE 2019

'An ice-cold skewering of patriarchy, humanity and the darkness of 20th century Europe' The Times

_________________________________

'It's like this, Saul Adler.'

'No, it's like this, Jennifer Moreau.'

In 1988, Saul Adler is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. Apparently fine, he gets up and poses for a photograph taken by his girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau. He carries this photo with him to East Berlin: a fragment of the present, an anchor to the West.

But in the GDR he finds himself troubled by time - stalked by the spectres of history, slipping in and out of a future that does not yet exist. Until, in 2016, Saul attempts to cross the Abbey Road again . . .

_________________________________

'A time-bending, location-hopping tale of love, truth and the power of seeing. Thoroughly gripping' Sunday Telegraph

'Writing so beautiful it stops the reader on the page' Independent

'Levy splices time in artfully believable, mesmerizing strokes' Lambda Literary

'Skewering totalitarianism - from the state, to the family, to the strictures of the male gaze - Levy explodes conventional narrative to explore the individual's place and culpability within history' Guardian

'An utterly beguiling fever dream' Daily Telegraph

From the Inside Flap

In 1989 Saul Adler ( a narcissistic, young historian) is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. He is apparently fine; he gets up and goes to see his art student girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau . They have sex then break up, but not before she has photographed Saul crossing the same Abbey Road. Saul leaves to study in communist East Berlin, two months before the Wall comes down. There he will encounter - significantly - both his assigned translator and his translator's sister, who swears she has seen a jaguar prowling the city. He will fall in love and brood upon his difficult, authoritarian father. And he will befriend a hippy, Rainer, who may or may not be a Stasi agent, but will certainly return to haunt him in middle age.

In 2016, Saul Adler is hit by a car on the Abbey Road. He is rushed to hospital, where he spends the following days slipping in and out of consciousness, and in and out of memories of the past. A number of people gather at his bedside. One of them is Jennifer Moreau. But someone important is missing.

Slipping slyly between time zones and leaving a spiralling trail, Deborah Levy's electrifying The Man Who Saw Everything examines what we see and what we fail to see, the grave crime of carelessness, the weight of history and our ruinous attempts to shrug it off.

--This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition.Review

“Deborah Levy's prose is light-handed and leaves a pleasant sting … in the new novel, Levy looks at masculinity through the point of view of Saul, a proud defector who sneers at 'authoritarian old men' like his father and the regimes they create, their dependence on walls, imaginative and real.” -Parul Sehgal, The New York Times

“Levy, as evidenced in Hot Milk (2016) and Swimming Home (2011), is a master of the seemingly loose yet actually taut story... As in her previous books, Levy's prose in The Man Who Saw Everything is controlled, refractive, sharply intelligent. There's no wasted motion. Single sentences render character with the clarity, and cruelty, of a snapshot...Love is unsettling, Levy suggests, and so is time, and so is sexuality, and so is the self. The Man Who Saw Everything, in its ghostly play of personal and political histories, bears witness to this truth.” -The Boston Globe

“In one short and sly book after another, [Levy] writes about characters navigating swerves of history and sexuality, and the social and personal rootlessness that accompanies both. If the themes sound weighty, Levy's elliptical fiction is the opposite, thanks in part to her wry appreciation of dramatic ironies at work. Her restless protagonists travel the Continent trying to forge an identity, only to discover that history has a way of laying traps for us-and also offering escapes when we least anticipate them. The Man Who Saw Everything, Levy's most stylistically complex novel yet. ... Levy's boldness, and her voice, are hard earned. ... Levy doesn't whisper in her fiction, but in her slim, elliptical books, she unspools big odysseys.” -The Atlantic

“Elliptical, elusive and endlessly stimulating… The Man Who Saw Everything is a brilliantly constructed jigsaw puzzle of meaning that will leave readers wondering how much they can ever truly know.” -The Washington Post

“Deborah Levy's novels are small masterworks of inlay, meticulously constructed. And The Man Who Saw Everything is perhaps her cleverest. But cleverness for its own sake is clearly not what interests her. Being human does. That is mystery enough, she repeatedly proves, as she tantalizes us with connections and secrets that seem to hover at the edge of our vision. Few writers, for example, can summon sadness with such force…Big ideas thud onto the page, like apples hitting the roof of that garden shed, but we hardly hear them. Deborah Levy makes us listen instead for the fragile rhythm of a breaking heart.” -Wall Street Journal

“Haunting and effective…Irresistible.” -Associated Press

“A work of philosophy and art... Each novel Man Booker finalist Deborah Levy writes comes nearer perfection.” -New York Journal of Books

“Deborah Levy, one of the most intellectually exciting writers in Britain today, has produced in this perplexing work a caustically funny exploration of history, perception, the nature of political tyranny and how lovers can simultaneously charm and erase each other.” -New York Times Book Review

“Levy's writing is playful, smart, and full of memorable lines.” -NPR.org

“Levy's deceivingly slim books are crammed with allusions to her literary progenitors: Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, but also Louise Bourgeois, Claude Chaun, and Cindy Sherman. For Levy is, above all, a visual writer, heaping image upon tantalizing image… Her novels are meticulously structured. They circle in on themselves, full of repetitions, allusions, and elisions whose logic unfailingly reveals itself at the end. With Levy, you are never quite sure of your footing. But she is… he experience of reading her is much like the jolt and pleasure of being submerged in water-resurfacing to find that the weather has turned.” -The New York Review of Books

“Longtime readers of Levy's work will know that she's just as capable of voyaging into the surreal and uncanny as she is documenting the social and psychological mores of her characters… you have a sense of a writer who's capable of nearly anything… a writer whose work has crossed boundaries of format and genre.” -Longreads

“Reading Deborah Levy's novels is a lesson in humility. She is a careful and intelligent writer with an absolute command of language, one who demands you not only to pay close attention, but also second-guess your immediate reactions and responses to her work. Her novels are deceptively slim in length, but supersized with profound ideas that defy preconceived notions and easy interpretations. The Man Who Saw Everything is just such a book, and reading it is the best possible sort of challenge” -Newsday

“A superbly crafted, enigmatic new story from an author of note…In a relatively short book, Levy spins an extraordinary web of connection, a dreamscape in which plangent images like a pearl necklace, a spilled drink, or the petals of a tree recur like soft chimes…Head-spinning and playful yet translucent, Levy's writing offers sophistication and delightful artistry. Levy defies gravity in a daring, time-bending new novel.” -Starred Review, Kirkus Reviews

“Booker Prize–finalist Levy (Hot Milk) explores the fragile connections and often vast chasms between self and others in this playful, destabilizing, and consistently surprising novel… Levy's novel brilliantly explores the parallels between personal and political history, and prompts questions about how one sees oneself-and what others see.” -Starred Review, Publishers Weekly

“The Man Who Saw Everything is bifurcated into two time periods: 1988 and 2016, but by Deborah Levy's deft hand and brilliant command of metaphor, the boundaries of space and time collapse. This is an extraordinary novel that captures the zeitgeist and specters of 20th-century Communism in such a way that far exceeds the 200 pages it is bound in.” -Shelf Awareness

“Audacious… compelling … the book [has] an understated power, as we confront a writer working against expectation to subvert the conventions of the novel, to rethink the form on her own terms.” -New Republic

“An evocative journey across a shape-shifting personal and political landscape. As Levy peels back each new layer of this at-times enigmatic story, there are new pleasures disclosed at every turn.” -Bookpage

“There is no way to succinctly summarize this slim book and adequately convey how it manages to hold exquisitely actual multiverses within its pages… A brilliant, blistering, bold look at identity, relationships, and time; a perfect puzzle of a novel.” -Nylon

“[An] utterly beguiling fever dream of a novel, which revisits aspects of Europe's authoritarian 20th-century history through the delirium of one man's shattered mind… Nominated for this year's Booker Prize, The Man Who Saw Everything is an intricate jigsaw, full of pieces that tantalizingly never quite fit together. . . In writing that is as clear as a stream yet also full of withheld meaning, Levy suggests that the grief and guilt inside Saul . . . is connected to Europe's legacy of persecution, paranoia, and totalitarianism.” -Daily Telegraph

“Deborah Levy's intelligent and supple latest novel, The Man Who Saw Everything, recently longlisted for the Booker Prize… is stunningly disorienting, fascinating . . . the balance shifts through Levy's skillful, dizzying storytelling.” -The Financial Times

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

‘I apologize,’ he said. ‘You walked on to the crossing and I slowed down, preparing to stop, but then you changed your mind and walked back to the kerb.’ His eyelids were quivering at the corners. ‘And then without warning you lurched forward on to the crossing.’ I smiled at his careful reconstruction of history, blatantly told in his favour. He furtively glanced at his car to check if it had been damaged. The wing mirror had shattered. His thin lips parted and hesighed sorrowfully, muttering something about how he had ordered the mirror from Milan. I had been up all night writing a lecture on the psychology of male tyrants and I’d made a start with the way Stalin flirted with women by flicking bread at them across the dinner table. My notes, about five sheets of paper, had fallen out of my leather sling bag and, embarrassingly, so had a packet of condoms. I started to pick them up. A small, flat, rectangular object was lying in the road. I noticed the driver was looking at my knuckles as I handed him the object, which felt warm and seemed to be vibrating in my palm. It was not mine soI assumed it was his. Blood dripped through my fingers. My palms were grazed and there was a cut on the knuckle of my left hand. I sucked it while he watched me, clearly distressed.

‘Do you need a lift somewhere?’

‘I’m okay.’

He offered to take me to a pharmacy to ‘clean up the wound’, as he put it. When I shook my head, he reached out his hand and touched my hair, which was strangely comforting. He asked for my name.

‘Saul Adler. Look, it’s just a small graze. I have thin skin. I always bleed a lot, it’s nothing.’

He was holding his left arm in a strange way, cradling it with his right arm. I picked up the condoms and shoved them into my jacket pocket. A wind was up. The leaves that had been swept into small piles under the trees were blowing across the road. The driver told me the traffic had been diverted because there was a demonstration that day in London, and he’d wondered if Abbey Road was closed off. The detour was not signposted clearly. He did not understand why he’d become confused, because he often came this way to watch the cricket at Lord’s, nearby. While he spoke, he gazed at the rectangular object in his hand.

The object was speaking. There was definitely a voice inside it, a man’s voice, and he was saying something angry and insulting. We both pretended not to hear his words.

Fuck off I hate you don’t come home

‘How old are you, Soorl? Can you tell me where you live?

’I think the near collision had really scared the driver.

When I told him I was twenty-eight, he didn’t believe me and asked for my age again. He was so posh he pronounced my name as if a pebble had been inserted between the roof of his mouth and his lower lip. His silver hair was slicked back with a product that made it shine.

I in turn asked for his name.

‘Wolfgang,’ he said very quickly, as if he did not want me toremember it.

‘Like Mozart,’ I said, and then, rather like a child showing his father where he’d been hurt after falling off a swing, I pointed to the cut on my knuckle and kept repeating that I was okay. His concerned tone was starting to make me tearful. I wanted him to drive off and leave me alone. Perhaps the tears were to do with my father’s recent death, though my father was not as groomed or as gentle as shiny, silver-haired Wolfgang. To hasten his departure, I explained that my girlfriend was about to arrive any minute now, so he didn’t have to hang around. In fact she was going to take a photograph of me stepping on to the zebra crossing in the style of the photograph on the Beatles album.

‘Which album is that, Soorl?’

‘It’s called Abbey Road. Everyone knows that. Where have youbeen, Wolfgang?’

He laughed but he looked sad. Perhaps it was because of the insultingwords that had been spoken from inside the vibrating object in his hand.

‘And how old is your girlfriend?’

‘Twenty-three. Actually, Abbey Road was the last album the Beatles recorded together at the EMI studios, which are just over there.’ I pointed to a large white house on the other side of the road.

‘Of course, I know that,’ he said sadly. ‘It’s nearly as famous as Buckingham Palace.’ He walked back to his car, murmuring, ‘Take care, Soorl. You’re lucky to have such a young girlfriend. By the way, what do you do?’

His comments and questions were starting to irritate me – also the way he sighed, as if he carried the weight of the world on the shoulders of his beige cashmere coat. I decided not to reveal that I was a historian and that my subject was communist Eastern Europe.

It was a relief to hear the animal growl of his engine revving as I stepped back on the pavement. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

User reviews

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to get Email Updates!

Thanks for subscribing.

Your response has been recorded.

India's Iconic & Independent Book Store offering a vast selection of books across a variety of genres Since 1978.

"We Believe In The Power of Books" Our mission is to make books accessible to everyone, and to cultivate a culture of reading and learning. We strive to provide a wide range of books, from classic literature, sci-fi and fantasy, to graphic novels, biographies and self-help books, so that everyone can find something to read.

Whether you’re looking for your next great read, a gift for someone special, or just browsing, Midland is here to make your book-buying experience easy and enjoyable.

We are shipping pan India and across the world.

For Bulk Order / Corporate Gifting

+91 9818282497 |

+91 9818282497 |  [email protected]

[email protected]

Click To Know More

INFORMATION

POLICIES

ACCOUNT

QUICK LINKS

ADDRESS

Shop No.20, Aurobindo Palace Market, Near Church, New Delhi